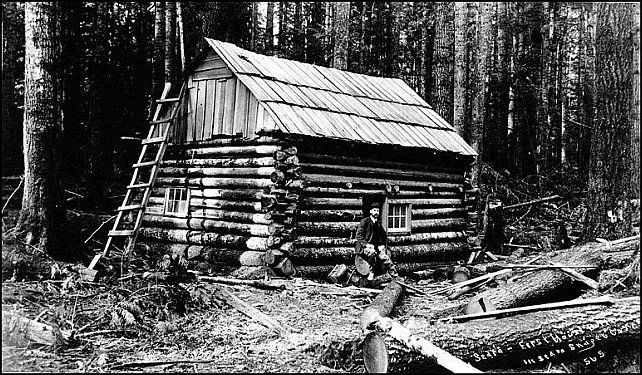

Years ago, the late Howard Miller showed me this copy below of what was one of the earliest photos of the future-Sedro area. It was taken by Arthur Churchill Warner in 1894 and he wrote on the photo: "First house built in Sedro, Skaget Co., Wash." By good fortune, the University of Washington Special Collections has the original (number WAR0593). Unfortunately we have not been discovered where the cabin was or who it belonged to. It could have belonged to any of the four British bachelors who homesteaded the future acreage or Sedro — Batey, Dunlop, Hart and Woods. Or it could have been David Batey's first cabin that he built near the Skagit River before he built his 2-story house a mile north on the bench. Or it could have been the cabin built by Lafayette Stevens at future Sterling, circa mid-1870s, or it could have been the one that Jesse Beriah Ball built near his mill at Sterling. Just like with the derivation of the name, Sterling, we may never know.

We researched Warner and discovered that he had a photo studio, Warner & Randolph, at Room 71, the Hinckley Building, at the corner of 2nd and Columbia streets, Seattle. Like many others, he came out to Washington Territory with the Northern Pacific Railroad, in 1886. Two years later, 1888, naturalist John Muir hired Warner to join and photograph a Mt. Rainier climbing expedition party that was guided by Philemon Beecher Van Trump, who was a member of the first successful ascent team in 1870. [See the Journal feature about that climb and William C. Ewing, founder of the Skagit News in 1884.] In 1890, Warner married Edith Randolph, the daughter of Captain Simon Peter Randolph, who supplied the capital for their business partnership. That resulted in a memorable series of Klondike Gold Rush photographs. The stress of living in the cold wilds of Alaska forced him to return to Seattle where he established a successful photography business that thrived until his death in 1943.Robert Monroe, curator of the UW Collection, learned that in 1925, Warner launched the Warner Projection Company, for which he created art deco projection slides to be used with cartoons and the lyrics of popular songs which might be projected on the theater screen so that audiences could join a pipe organist's renditions of popular songs. He and his wife also established a lecture business; he made the photographs and she tinted the glass slides by hand in the days before color photography.

|